Inventing a New Musical Instrument Before You Are 20 Years Old

Thomas Moore – tmoore@rollins.edu

Joshua Almond – jalmond@rollins.edu

Daniel Crozier – dcrozier@rollins.edu

Rollins College

Winter Park, FL 32707

Popular version of paper 2aMU1 presented at the 166th ASA Meeting, 2013 in San Francisco, CA.

True interdisciplinary scholarship is difficult to perform and even harder to teach. The disciplinary boundaries inherent in higher education keep the arts and sciences separate, with the result being that most students see education as a compartmentalized endeavor. You learn art in the art studio, science in the science lab, and music in the music building. However, during the 2012-13 academic year a few students at Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida, broke down these disciplinary walls and pursued interdisciplinary learning at a deep level in a course entitled Soundscapes.

The class, in which a small number of students from a variety of academic majors enrolled, required that the students design and build unique musical instruments based on the application of the theories of acoustical physics. But in addition to making a working musical instrument, they were also required to design them so that they were visually interesting enough to be displayed in an art gallery. Furthermore, they had to ensure the instruments played notes of the Western musical scale and that the timbres of the instruments allowed them to be played together in an ensemble. Finally, the students were required to compose original music for ensembles of these instruments and play them in a public concert in the college’s concert hall.

The students who participated in the experimental course were all sophomores in the honors program at Rollins, but there were no other requirements. Therefore, students with a variety of backgrounds and academic majors were represented. However, of the students who enrolled in the course there were none majoring in physics or art, and only one was majoring in music. None had previous experience in design or construction in wood or metal, none had more than a high school education in physics, and only a few could even read music when the class began in August 2012.

Three faculty members collaborated in teaching the course, which was made possible by a faculty development grant from the Associated Colleges of the South and the Mellon Foundation. The faculty included a physics professor who helped the students understand the physics of musical instruments and provided guidance in the calculations and experimentation required to ensure that the instruments played notes with pitches found in the Western musical scales; a sculptor who guided the students through the artistic design process, taught them the construction techniques required to build in wood and metal, and supervised the building process; and a composer who taught the students some basic musical theory, guided them in the crafting and notation of their musical compositions, and assisted them in learning how to perform music on their instruments.

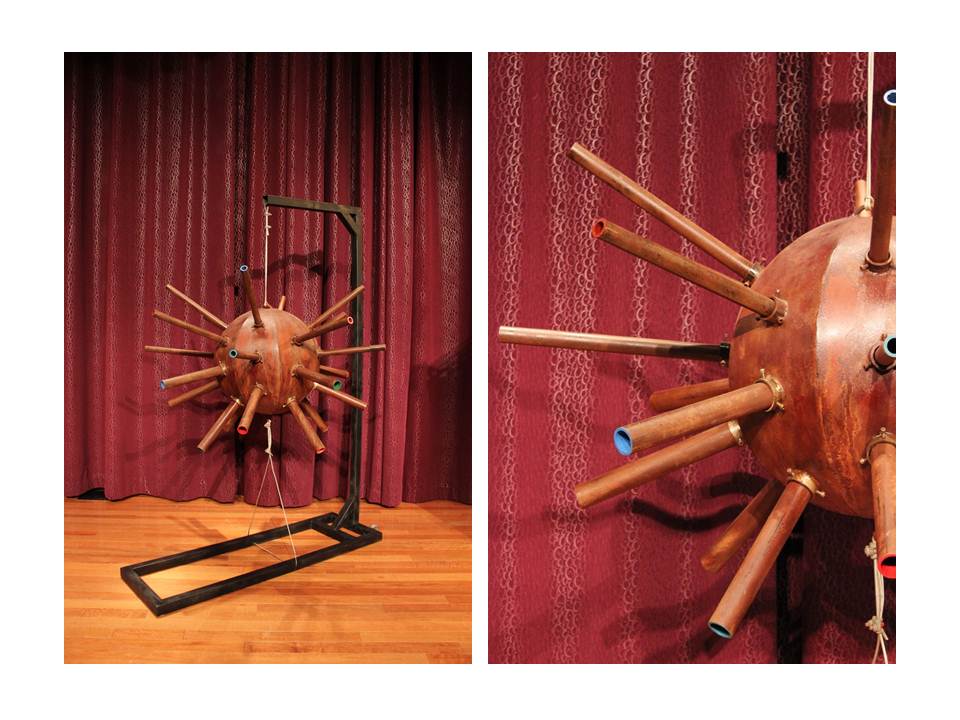

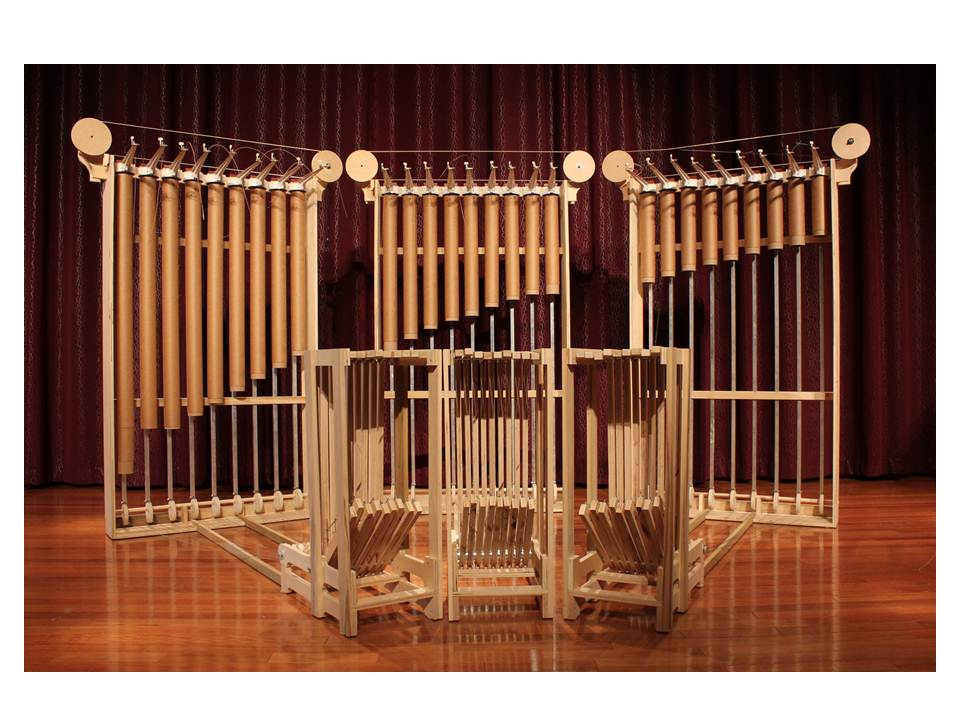

In April 2013, eight months after their first meeting, the students premiered five original musical works performed on eight original musical instruments in the Tiedtke concert hall on the campus of Rollins College. The instruments were truly unique and included such original ideas as a large sphere with tuned pipes that looks similar to a mid-20th century underwater mine, shown in Figure 1; a bowed string instrument controlled by a keyboard, shown in Figure 2; and an instrument that uses the performer’s voice to vibrate strings attached to a soundboard, shown in Figure 3. Figure 4 is a photograph from the concert showing four of the students performing an original work for five of the instruments, which can be heard here. Another of the six original works that were premiered at the concert can be heard here.

The purpose of the course was to demonstrate an integrated approach to education that can be expanded to include almost any collection of diverse fields of study. The necessity of learning art, music and physics within a broader context made the subject-specific knowledge more meaningful to the students; however, anonymous feedback from the students indicated that the most important lessons concerned the value of pursing original scholarship, the value of tenacity and hard work, and the importance of confidence in one’s own ability when faced with a seemingly impossible task.

Fig. #1: The Cantesól is a 30-inch diameter metal resonating chamber with tuned pipes protruding from the shell. The instrument can be played by striking the pipes transversely or longitudinally.

Fig. #2: Each of the three individual segments of this instrument has a moving belt at the top that acts as a bow. When a key is pressed, a pulley and cam arrangement raises a taught string to make contact with the moving belt. The strings are tuned to the Western chromatic scale and each pipe is cut to a length so that the pipe resonance coincides with the string resonance.

Fig. #3: This instrument requires the performer to sing into a microphone. The signal from the microphone is amplified and sent through a series of six wires of different lengths that are strung over individual wooden bridges resting on a sound board. Each wire is in a strong magnetic field created by a set of high field strength magnets; the current in the magnetic field causes the wires to vibrate in response to the frequencies present in the singer’s voice.

Fig. #4: Four students performing one of the original musical works in concert.